In Android development, startup speed is a critical metric, and optimization is a vital process. The core philosophy of startup optimization is “doing less” during launch. Typical practices include:

- Asynchronous Loading

- Delayed Loading (DelayLoad)

- Lazy Loading

Most developers who have worked on startup optimization have likely used these. This article dives deep into a specific implementation of DelayLoad and the underlying principles. While the code itself is simple, the mechanics involve Looper, Handler, MessageQueue, VSYNC, and more. I’ll also share some edge cases and my own reflections.

1. Implementation of Optimized DelayLoad

When people think of DelayLoad, they usually think of Handler.postDelayed in onCreate. While convenient, it has one fatal flaw: How long should the delay be?

On high-end devices, apps launch incredibly fast, requiring only a short delay. On low-end devices, the launch takes much longer. Using a fixed delay leads to inconsistent user experiences across different hardware.

Here is the optimized solution:

- Create a

Handlerand aRunnablefor UI updates.

1 | private Handler myHandler = new Handler(); |

- Add the following code to your main Activity’s

onCreate:

1 | getWindow().getDecorView().post(new Runnable() { |

The implementation is surprisingly simple. Let’s compare it with other common approaches.

2. Comparison of Three Approaches

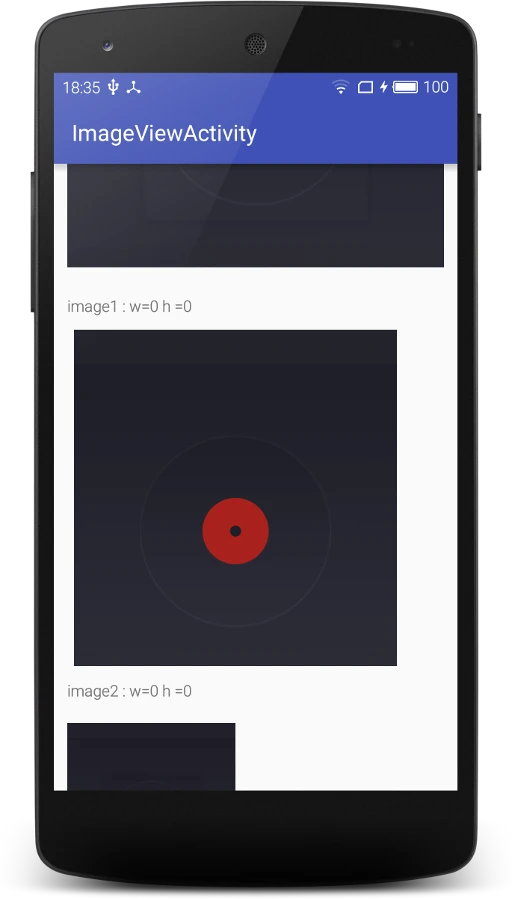

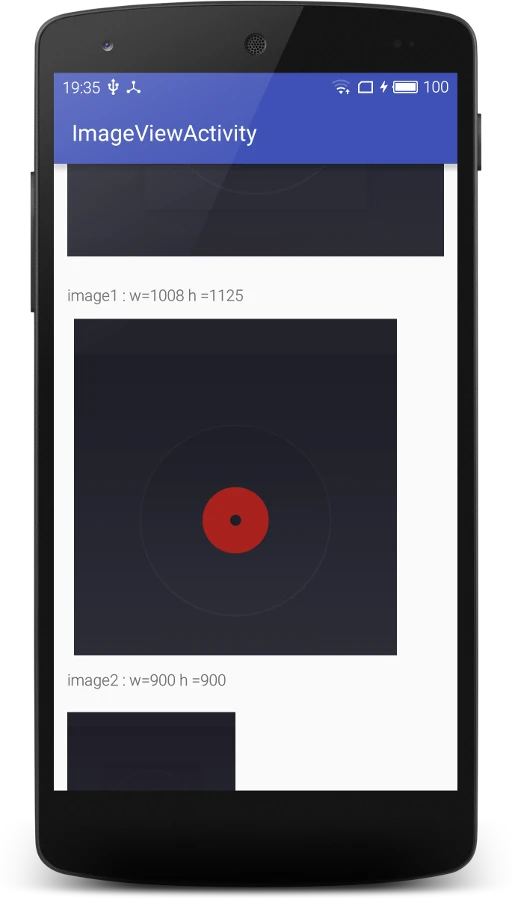

To verify the effectiveness of this optimized DelayLoad, we created a test app with three images of different sizes. Below each image is a TextView to display its dimensions.

1 | public class MainActivity extends AppCompatActivity { |

We focus on:

- When is

updateTextexecuted? - Are the dimensions correctly displayed?

- Is there a “DelayLoad” effect (executing after initial frame rendering)?

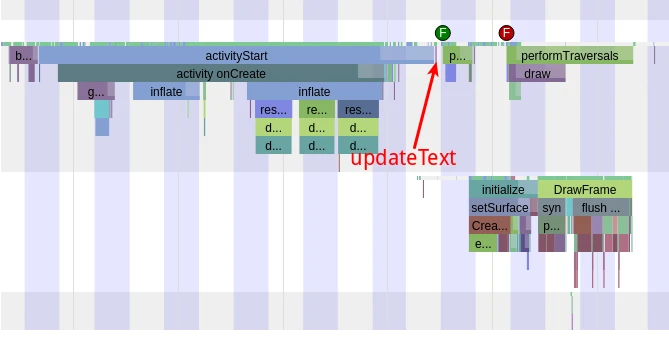

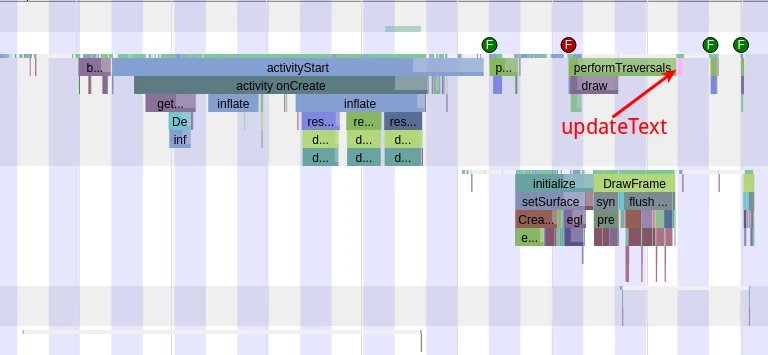

2.1 Approach 1: Immediate Post

When is it executed?

updateText runs immediately after the onCreate/onStart/onResume lifecycle callbacks.

Are dimensions correct?

No, the width and height are 0. This is because lifecycle callbacks don’t perform Measure or Layout; those happen later in performTraversals.

Is there a DelayLoad effect?

No. The app’s first frame is only shown after two performTraversals cycles. Since updateText runs before the first cycle, its execution time is “penalized” against the startup time.

2.2 Approach 2: PostDelayed (300ms)

When is it executed?

updateText runs after the first frame is displayed. A subsequent performTraversals then updates the TextViews.

Are dimensions correct?

Yes. Since it runs after performTraversals, geometry data is available.

Is there a DelayLoad effect?

Yes, but it’s hit-or-miss. If the delay is 300ms, the text updates 170ms after the first frame. If the task were a heavy UI component, the user would see a jarring “blank-to-content” pop-in. If you reduce the delay to 50ms to prevent the pop-in, it might run before the first frame on slower devices, defeating the purpose.

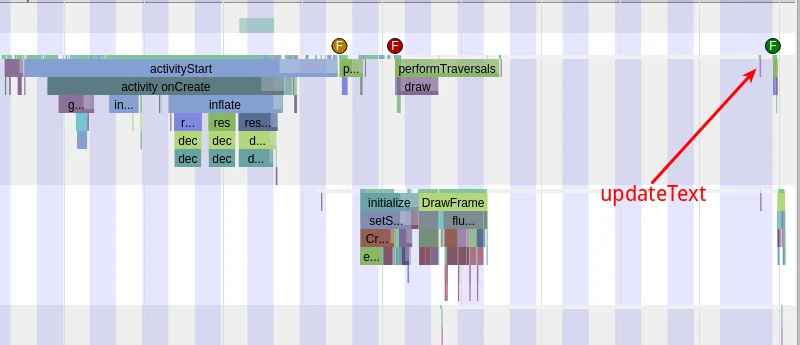

2.3 Approach 3: Optimized DelayLoad

We want updateText to run precisely after the app’s first frame is visible to the user—no sooner, no later.

When is it executed?

updateText runs immediately after the second performTraversals finishes. The TextView updates with the very next VSYNC signal.

Are dimensions correct?

Yes, perfectly.

Is there a DelayLoad effect?

Yes. It ensures data is loaded as soon as possible after the UI is visible, without guessing a delay time.

3. Reflections

The code for this optimization is incredibly simple, but its effectiveness is profound. To understand why this works, we need to dig into lower-level components like Looper, Handler, VSYNC, and ViewRootImpl. I’ll explore these principles in the next part of this series.

4. Code

The sample code is available on GitHub: https://github.com/Gracker/DelayLoadSample

About Me && Blog

(Links and introduction)