This is the seventh article in the Perfetto series, focusing on MainThread (UI Thread) and RenderThread, the two most critical threads in any Android application. This article will examine the workflow of MainThread and RenderThread from Perfetto’s perspective, covering topics such as jank, software rendering, and frame drop calculations.

As Google officially promotes Perfetto as the replacement for Systrace, Perfetto has become the mainstream choice in performance analysis. This article combines specific Perfetto trace information to help readers understand the complete workflow of MainThread and RenderThread, enabling you to:

- Accurately identify key trace tags: Understand the roles of critical threads like UI Thread and RenderThread

- Understand the complete frame rendering process: Every step from Vsync signal to screen display

- Locate performance bottlenecks: Quickly find the root cause of jank and performance issues through trace information

Table of Contents

- Series Catalog

- Rendering Flow Analysis Based on Perfetto

- Evolution of Dual-Thread Rendering Architecture

- Main Thread Creation Process

- ActivityThread Functionality

- RenderThread Creation and Development

- Performance

- Perfetto’s Unique FrameTimeline Feature

- Vsync Signals in Perfetto

- References

- Attachments

- About Me && Blog

Series Catalog

- Android Perfetto Series Catalog

- Android Perfetto Series 1: Introduction to Perfetto

- Android Perfetto Series 2: Capturing Perfetto Traces

- Android Perfetto Series 3: Familiarizing with Perfetto View

- Android Perfetto Series 4: Opening Large Traces via Command Line

- Android Perfetto Series 5: Android App Rendering Flow Based on Choreographer

- Android Perfetto Series 6: Why 120Hz? Advantages and Challenges of High Refresh Rates

- Android Perfetto Series 7: MainThread and RenderThread Deep Dive

- Android Perfetto Series 8: Understanding Vsync Mechanism and Performance Analysis

- Android Perfetto Series 9: CPU Information Interpretation

- Android Perfetto Series 10: Binder Scheduling and Lock Contention

- Video (Bilibili) - Android Perfetto Basics and Case Sharing

- Video (Bilibili) - Android Perfetto: Trace Graph Types - AOSP, WebView, Flutter + OEM System Optimization

If you haven’t read the Systrace series yet, here are the links:

- Systrace Series Catalog: A systematic introduction to Systrace, Perfetto’s predecessor, and learning about Android performance optimization and Android system operation basics through Systrace.

- Personal Blog: My personal blog, mainly Android-related content, with some life and work-related content as well.

Welcome to join the WeChat group or community on the About Me page to discuss your questions, what you’d most like to see about Perfetto, and all Android development-related topics with fellow group members.

The trace files used in this article have been uploaded to Github: https://github.com/Gracker/SystraceForBlog/tree/master/Android_Perfetto/demo_app_aosp_scroll.perfetto-trace, feel free to download them.

Note: This article is based on Android 16’s latest rendering architecture

Rendering Flow Analysis Based on Perfetto

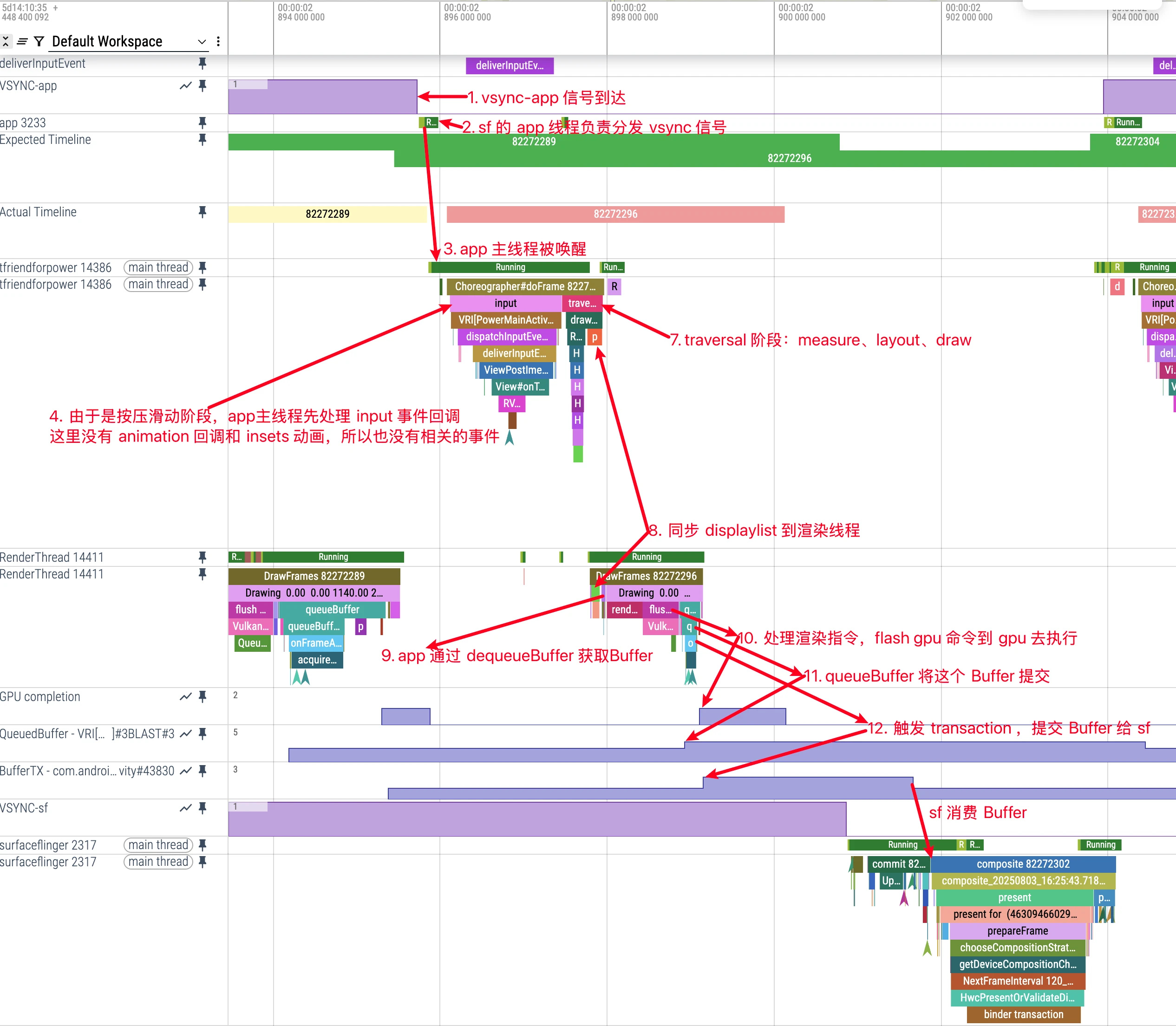

Using a scrolling list as an example, we’ll capture the workflow of the main thread and render thread for one frame through Perfetto (each frame follows this process, though some frames have more work to do than others). In the Perfetto UI, focus on observing the activities of the “UI Thread” and “RenderThread” threads.

Frame Concept and Basic Parameters

Before analyzing Perfetto traces, you need to understand the basic concept of frames. The Android system refreshes screen content at fixed time intervals:

- 60Hz devices: Refresh every 16.67ms, 60 frames per second

- 90Hz devices: Refresh every 11.11ms, 90 frames per second

- 120Hz devices: Refresh every 8.33ms, 120 frames per second

When analyzing rendering performance in Perfetto, focus on these two threads:

- UI Thread: The application main thread, handling user input, business logic, and layout calculations

- RenderThread: The rendering thread, executing GPU rendering commands and interacting with SurfaceFlinger

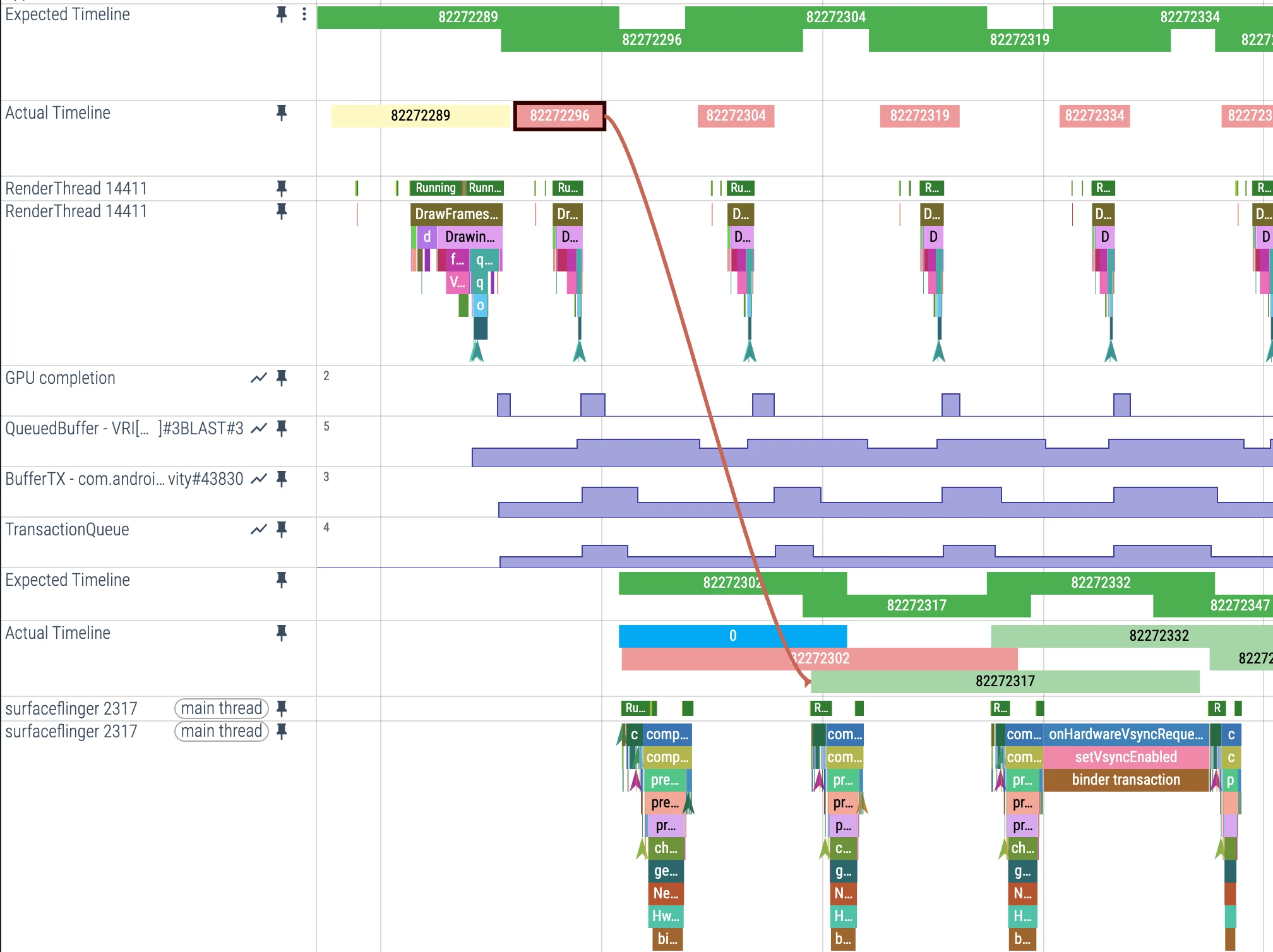

Main Thread and RenderThread Workflow

Through the Perfetto screenshot above, you can see the complete rendering process for one frame. We can imagine the Perfetto diagram as a river: the main thread handles logic upstream, and the render thread executes drawing downstream. The river flows from left to right, with each segment representing a step.

Important Note: Not every frame executes all steps. Input, Animation, and Insets Animation are all on-demand. Traversal (measure, layout, draw) is also on-demand: only when requestLayout, invalidate, window attribute changes, or visibility changes happen will scheduleTraversals() post CALLBACK_TRAVERSAL. In continuous scrolling/animation scenarios, it often looks like it runs every frame.

Try to “play” this complete process in your mind through the following description:

1. Main Thread Waits for Vsync Signal

- Perfetto trace: Main thread in Sleep state (shown as idle block)

- Process description: Main thread waits for the vertical sync signal (Vsync) to arrive, ensuring rendering synchronizes with screen refresh rate to avoid screen tearing

2. Vsync-app Signal Delivery Process

- Perfetto trace:

vsync-apprelated events, SurfaceFlinger app thread activity - Process description: When hardware generates a Vsync signal, it’s first delivered to SurfaceFlinger. SurfaceFlinger’s app thread is awakened, responsible for managing and distributing Vsync signals to applications that need to render. This intermediary layer design allows for system-level Vsync scheduling and optimization

Important Notes:

- Vsync-app is requested on-demand: Apps only receive vsync-app signals when actively requested; no request means no signal

- Multi-app sharing mechanism: Multiple apps may request vsync-app signals simultaneously

- Signal attribution issue: The vsync-app signal in SurfaceFlinger may be requested by other apps; if the currently analyzed app hasn’t requested it, there will be no frame output, which is normal

3. SurfaceFlinger Wakes Up App Main Thread

- Perfetto trace:

FrameDisplayEventReceiver.onVsync - Process description: SurfaceFlinger sends the Vsync signal to registered apps through the FrameDisplayEventReceiver mechanism. The app’s Choreographer receives the signal and begins the frame drawing process

4. Processing Input Events (Input)

- Perfetto trace:

Inputblock - Process description: Only executes when there are input events, mainly handling touch, scroll, and other user interactions

- Trigger conditions:

- Has Input callback: When finger presses and slides on screen (like list scrolling, page dragging)

- No Input callback: During inertial scrolling after finger lift, static state

- Note: Input callback is determined by the previous frame’s user interaction behavior to decide whether to execute in the current frame

5. Processing Animations (Animation)

- Perfetto trace:

Animationblock - Process description: Only executes when animations need updating, updates animation state and current frame’s animation values

- Trigger conditions:

- Has Animation callback: During inertial scrolling, property animations running, list item creation and content changes, page transition animations, etc.

- No Animation callback: Interface static state, pure Input interaction phase (when no animation effects)

- Note: Animation callback is also determined by callbacks posted in the previous frame to decide whether to execute in the current frame

6. Processing Insets Animations

- Perfetto trace:

Insets Animationblock - Process description: Only executes when window inset changes occur, handles window boundary animations

- Trigger conditions:

- Has Insets Animation callback: Keyboard show/hide, status bar show/hide, navigation bar changes, etc.

- No Insets Animation callback: Window boundary stable state, most common interaction scenarios

7. Traversal (Measure, Layout, Draw Preparation)

- Perfetto trace:

performTraversals,measure,layout,draw - Process description: These are the three core UI rendering stages, but they do not run as a complete set on every Vsync. Execution depends on whether the current frame has layout/draw requests.

7.1 Measure Phase

- Purpose: Determine the size of each View

- Process: Starting from the root View, recursively measure the width and height of all child Views

- Key concepts:

MeasureSpec: Encapsulates parent container’s size requirements for child Views (EXACTLY, AT_MOST, UNSPECIFIED)onMeasure(): Each View overrides this method to implement its own measurement logic

- Perfetto representation:

measureevent, duration depends on View hierarchy complexity

7.2 Layout Phase

- Purpose: Determine each View’s position coordinates in the parent container

- Process: Based on Measure phase results, assign actual display positions to each View

- Key concepts:

layout(left, top, right, bottom): Set View’s four boundary coordinatesonLayout(): ViewGroup overrides this method to determine child View positions

- Perfetto representation:

layoutevent, usually faster than measure

7.3 Draw Phase

- Purpose: Draw View content onto canvas

- Modern implementation: Doesn’t directly draw pixels, but builds DisplayList (drawing instruction list)

- Key process:

draw(Canvas): Draw View’s own contentonDraw(Canvas): Subclass overrides to implement specific drawing logicdispatchDraw(Canvas): ViewGroup uses this to draw child Views

- Perfetto representation:

drawevent, mainly builds DisplayList under hardware acceleration

ViewRootImpl.performTraversals Core Code

1 | // frameworks/base/core/java/android/view/ViewRootImpl.java |

Note: In latest AOSP,

performTraversalsis much more complex (relayout, surface changes, sync groups, canceled draws, visibility, etc.). The snippet keeps only the flow directly related to Measure/Layout/Draw.

Execution conditions for the three phases:

- Measure: Runs on first draw and when layout/configuration/insets/window changes require it, not fixed every frame

- Layout: Runs when

layoutRequestedis true and the app is in a drawable state - Draw: Runs only when draw conditions are satisfied; canceled/pre-draw-blocked cases reschedule traversal

8. Sync DisplayList to Render Thread

- Perfetto trace: syncAndDrawFrame, visible “sync” or “syncAndDrawFrame” event (usually shown as data transfer point from main thread to render thread)

- Process description: Main thread syncs current-frame RenderNode/DisplayList state to RenderThread through

syncAndDrawFrame. This is not pure fire-and-forget async: UI thread waits briefly for a key sync point (DrawFrameTask::postAndWait) and is then unblocked as early as possible; it does not wait until the frame is actually presented.

9. Render Thread Acquires Buffer

- Perfetto trace: You can often observe

DequeueBufferDuration/QueueBufferDurationrelated data (exact tags vary by Android version and OEM). - Process description: During draw submission, RenderThread goes through the

ANativeWindow/RenderPipelinepath for buffer acquire/swap. Whether it waits, and how long it waits, directly affects deadline miss risk.

10. Process Rendering Instructions and Flush to GPU

- Perfetto trace:

drawingrelated blocks - Process description: RenderThread (CPU side) processes the RenderNode tree synced from UI thread via

HardwareRenderer/CanvasContext, builds GPU commands, and submits them. GPU executes asynchronously and produces fences for downstream composition sync.

11. Submit Buffer (Possibly Unsignaled)

- Perfetto trace: queueBuffer (can observe acquireFence state)

- Process description: Frame submission enters SurfaceFlinger through BufferQueue/BLAST. In some scenarios, unsignaled-fence behavior appears (policy-controlled), aiming to reduce end-to-end latency.

12. Trigger Transaction to SurfaceFlinger

- Perfetto trace: TransactionQueue or BLAST transaction events, generally after queueBuffer, some traces don’t have this tag

- Process description: App side associates buffer and layer-property updates via BLAST/SurfaceControl transactions and submits them to SurfaceFlinger. SurfaceFlinger then decides latch timing based on

LatchUnsignaledConfigand related policies, composes, and presents.

Identifying different rendering modes in Perfetto:

- During finger sliding: Each frame has complete

Input→Traversal→RenderThreadchain - During inertial scrolling: Each frame has

Animation→Traversal→RenderThread, noInput - In static state: Occasionally appears

Animation→Traversal→RenderThread, noInput

Software Drawing vs Hardware Acceleration

Although hardware-accelerated rendering is now basically standard, understanding the differences between the two rendering modes still helps understand Perfetto traces:

| Aspect | Software Drawing | Hardware Acceleration |

|---|---|---|

| Drawing Thread | Main thread | RenderThread |

| Drawing Engine | Skia (CPU) | OpenGL/Vulkan (GPU) |

| Perfetto Characteristics | Main thread has large draw events |

Main thread completes quickly, RenderThread handles drawing |

| Performance Impact | May block main thread | Asynchronous rendering, better performance |

The above introduces the basic rendering process. For more detailed Choreographer principles, refer to Android Perfetto Series 5: Android App Rendering Flow Based on Choreographer.

Next, we’ll focus on in-depth content about the main thread and render thread:

- Main thread development

- Main thread creation

- Render thread creation

- Division of labor between main thread and render thread

Evolution of Dual-Thread Rendering Architecture

Android’s rendering system has undergone an important evolution from single-thread to dual-thread.

Single-Thread Era (Before Android 4.4)

In early Android versions, all UI-related work was executed on the main thread:

- Processing user input events

- Executing measure, layout, draw

- Calling OpenGL for actual drawing

- Interacting with SurfaceFlinger

Problems with this design:

- Poor responsiveness: Main thread overloaded, prone to ANR

- Performance bottleneck: CPU and GPU cannot work in parallel

- Unstable frame rate: Complex interfaces easily cause frame drops

Dual-Thread Era (Starting from Android 5.0 Lollipop)

Android 5.0 introduced RenderThread, implementing separation of rendering work:

Main Thread Responsibilities:

- Processing user input and business logic

- Executing View’s measure, layout, draw

- Building DisplayList (drawing instruction list)

- Synchronizing data with render thread

Render Thread Responsibilities:

- Receiving and processing DisplayList

- Executing OpenGL/Vulkan rendering commands

- Managing textures and rendering resources

- Interacting with SurfaceFlinger

Advantages of this architecture:

- Parallel processing: Main thread can process next frame while render thread works

- Improved responsiveness: Main thread no longer blocked by rendering

- Performance optimization: Better utilization of GPU resources

Main Thread Creation Process

Android App processes are Linux-based, and their management is also based on Linux process management mechanisms, so their creation also calls the fork function

frameworks/base/core/jni/com_android_internal_os_Zygote.cpp

1 | pid_t pid = fork(); |

The forked process, we can consider it as the main thread here, but this thread hasn’t connected with Android yet, so it cannot handle Android App Messages; since Android App threads run based on the message mechanism, this forked main thread needs to bind with Android’s Message messaging to handle various Android App Messages.

This introduces ActivityThread. To be precise, ActivityThread should be named ProcessThread more appropriately. ActivityThread connects the forked process with App Messages, and their cooperation forms what we know as the Android App main thread. So ActivityThread is actually not a Thread, but it initializes the MessageQueue, Looper, and Handler required by the Message mechanism, and its Handler handles most Message messages, so we habitually think ActivityThread is the main thread, but it’s actually just a logical processing unit of the main thread.

ActivityThread Creation

After app process fork, the main path is:ZygoteConnection.handleChildProc → ZygoteInit.zygoteInit → RuntimeInit.applicationInit → ActivityThread.main

com/android/internal/os/ZygoteConnection.java

1 | private Runnable handleChildProc(ZygoteArguments parsedArgs, FileDescriptor pipeFd, |

For regular app processes, this goes through zygoteInit and eventually reaches ActivityThread.main. childZygoteInit is for child-zygote flow, not the normal app path.

android/app/ActivityThread.java

1 | public static void main(String[] args) { |

The comments are very clear, so I won’t elaborate here. After the main function finishes processing, the main thread is officially online and starts working.

ActivityThread Functionality

Also, what we often say is that Android’s four major components all run on the main thread. This is actually easy to understand by looking at ActivityThread’s Handler Messages

1 | class H extends Handler { // Excerpt of some, based on Android 16 latest implementation |

You can see that process creation, Activity startup, Service management, Receiver management, and Provider management are all handled here, then proceed to specific handleXXX

RenderThread Creation and Development

After discussing the main thread, let’s talk about the render thread, which is RenderThread. The earliest Android versions didn’t have a render thread; rendering work was all done on the main thread using CPU, calling the libSkia library. RenderThread was a new component added in Android Lollipop, responsible for taking on part of the main thread’s previous rendering work, reducing the main thread’s burden.

Software Drawing

What we generally refer to as hardware acceleration means GPU acceleration, which can be understood as using RenderThread to call GPU for rendering acceleration. Hardware acceleration is enabled by default in current Android, so if we don’t set anything, our processes will have both main thread and render thread by default (with visible content). If we add this to the Application tag in the App’s AndroidManifest:

1 | android:hardwareAccelerated="false" |

We can disable hardware acceleration. When the system detects that your App has disabled hardware acceleration, it won’t initialize RenderThread and will directly use CPU to call libSkia for rendering. Its Trace tracking performance is as follows (resources are older, using Systrace diagram)

Compared with the Perfetto diagram with hardware acceleration enabled at the beginning of this article, you can see that the main thread takes longer to execute because it needs to perform rendering work, making it more prone to jank. At the same time, the idle interval between frames becomes shorter, compressing the execution time of other Messages. In Perfetto, this difference can be clearly observed through the length and density of thread activity.

Hardware-Accelerated Drawing

Under normal circumstances, hardware acceleration is enabled. Main thread draw mainly builds/updates DisplayList (RenderNode tree), then syncs via syncAndDrawFrame. UI thread waits briefly on key sync path, returns quickly to process messages, and RenderThread continues rendering/submission.

Render Thread Initialization

Render thread initialization occurs when content actually needs to be drawn. Generally, when we start an Activity, during the first draw execution, it checks whether the render thread is initialized; if not, it proceeds with initialization

android/view/ViewRootImpl.java

1 | // Render thread initialization |

The BlastBufferQueue created here will play a key role in subsequent rendering processes:

- Provides efficient Buffer management for RenderThread

- Supports batch Transaction submission, reducing interaction overhead with SurfaceFlinger

- QueuedBuffer metric changes can be observed in Perfetto

Subsequently, draw is called directly

android/view/ThreadedRenderer.java

1 | mAttachInfo.mThreadedRenderer.draw(mView, mAttachInfo, this); |

The draw above updates DisplayList first, then calls syncAndDrawFrame for the key UI Thread to RenderThread sync stage.

UI Thread and RenderThread DisplayList Synchronization Mechanism

In the syncAndDrawFrame key function, the following important synchronization operations occur:

1 | // frameworks/base/libs/hwui/renderthread/RenderProxy.cpp |

syncAndDrawFrame is not fully non-blocking. In latest AOSP, DrawFrameTask::drawFrame() calls postAndWait(): it posts work to RenderThread queue and then waits on a condition variable; RenderThread unblocks UI at an appropriate sync point. So this is “wait a bit, unblock UI as early as possible”, not “UI never waits”.

1 | // frameworks/base/libs/hwui/renderthread/DrawFrameTask.cpp |

The specific synchronization process includes:

- RenderNode tree transfer: The RenderNode tree (containing DisplayList) built by the main thread during the draw process is passed to RenderThread

- Property synchronization: View’s transformation matrices, transparency, clipping regions, and other properties are synchronized together

- Resource sharing: Drawing resources like textures, Paths, and Paints establish sharing mechanisms between the two threads

- Rendering state transfer: Rendering state information needed for the current frame is passed to RenderThread

This synchronization process is the core of Android hardware-accelerated rendering. It implements a division of labor where UI Thread focuses on logic processing and RenderThread focuses on rendering.

The core implementation of the render thread is in the libhwui library, with code located at frameworks/base/libs/hwui

RenderThread and BlastBufferQueue Interaction Flow

After RenderThread receives the synced DisplayList, it begins actual rendering work. During this process, it interacts closely with BlastBufferQueue:

1 | // frameworks/base/libs/hwui/renderthread/CanvasContext.cpp |

Note: The old intuitive flow (

dequeueBuffer/queueBuffer/flushTransaction) is still useful as a mental model, but in latest mainline these details are consolidated intoRenderPipeline/ANativeWindowpath, andCanvasContext::draw()is no longer in the old shape.

Key Features of BlastBufferQueue:

- App-side management: Unlike traditional BufferQueue created by SurfaceFlinger, BlastBufferQueue is created and managed by the App side

- Reduced sync waiting: Through producer-consumer model, reduces RenderThread’s wait time during dequeueBuffer

- Efficient buffer rotation: Supports smarter buffer management strategies, especially adapted for high refresh rate displays

- Asynchronous submission: Asynchronously submits completed frames to SurfaceFlinger through transaction mechanism

- Supports unsignaled buffer: Cooperating with SurfaceFlinger unsignaled-latch policies can reduce end-to-end latency in specific scenarios

In-depth Discussion on Latching Unsignaled Buffers

Modern Android systems have fine-grained control over presentFence handling, not always waiting. This mechanism is called “Latching Unsignaled Buffers” (capturing unready buffers).

Traditional mode: SurfaceFlinger must wait for App’s

presentFenceto be signaled by GPU before it can “latch” (capture) this Buffer for composition. This ensures safety but increases latency.Latch Unsignaled mode: In this mode, SurfaceFlinger can immediately latch a Buffer that GPU hasn’t finished rendering (i.e., fence unsignaled) and start partial composition work early. When it needs to actually use this Buffer’s content, it waits for

presentFenceinternally. This further hides GPU rendering latency through pipelining, crucial for reducing input latency in fullscreen apps like games and videos.

Control Switch and Policy (Android 13+):

This behavior can be globally debugged through system property debug.sf.auto_latch_unsignaled, but more importantly, it’s controlled by a layered policy called LatchUnsignaledConfig. A typical policy is AutoSingleLayer:

- When only a single layer on screen is updating (like fullscreen games or videos), the system automatically enables Latch Unsignaled mode, as there are no complex layer dependencies at this time, lowest risk, maximum benefit.

- When multiple layers are updating, the system falls back to safer traditional waiting mode to avoid potential visual errors.

Therefore, SurfaceFlinger doesn’t always blindly wait for presentFence, but decides whether to “jump the gun” based on precise policies, achieving a balance between stability and ultimate performance.

Division of Labor Between Main Thread and Render Thread

The main thread handles process Messages, Input events, Animation logic, Measure, Layout, Draw, and updates DisplayList, but doesn’t directly interact with SurfaceFlinger; the render thread handles rendering-related work, including interaction with BlastBufferQueue, GPU rendering command execution, and final interaction with SurfaceFlinger.

When hardware acceleration is enabled, in the Draw phase of Measure, Layout, Draw, Android uses DisplayList for drawing rather than directly using CPU to draw each frame. DisplayList is a record of a series of drawing operations, abstracted as the RenderNode class. The advantages of this indirect drawing operation are as follows:

- DisplayList can be drawn multiple times on demand without interacting with business logic

- Specific drawing operations (like translation, scale, etc.) can be applied to the entire DisplayList without redistributing drawing operations

- When all drawing operations are known, they can be optimized: for example, all text can be drawn together at once

- Processing of DisplayList can be transferred to another thread (i.e., RenderThread)

- After sync ends, the main thread can process other Messages without waiting for RenderThread to finish

- Through BlastBufferQueue, achieve more efficient buffer management, reducing rendering latency and main thread blocking

BlastBufferQueue Working Principle

BlastBufferQueue is a key component in modern Android rendering architecture, changing traditional buffer management methods:

Traditional BufferQueue vs BlastBufferQueue:

Different creation entities:

- Traditional BufferQueue: Created and managed by SurfaceFlinger

- BlastBufferQueue: Created and managed by App side (ViewRootImpl)

Buffer acquisition mechanism:

- Traditional method: RenderThread needs to request Buffer from SurfaceFlinger through Binder call, may block if no available Buffer

- BlastBufferQueue: App side pre-manages buffer pool, RenderThread can acquire Buffer more efficiently

Submission mechanism:

- Traditional method: Directly submits to SurfaceFlinger through queueBuffer

- BlastBufferQueue: Batch submits through transaction mechanism, reducing Binder call overhead

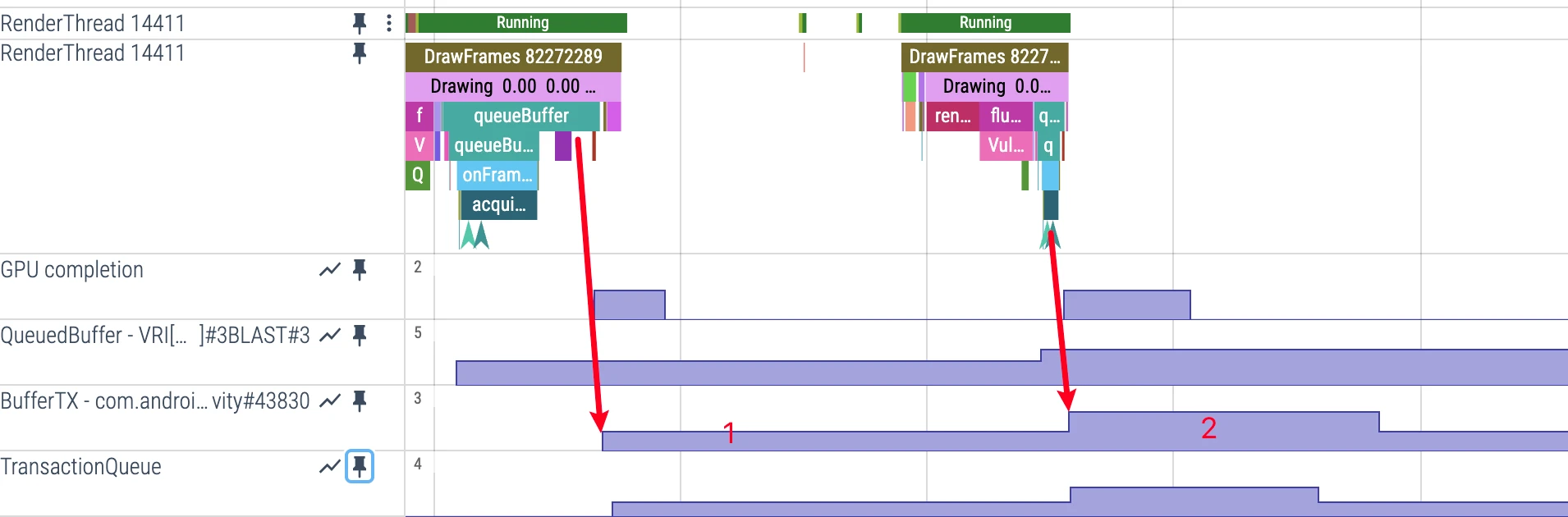

Observing BlastBufferQueue in Perfetto:

In Perfetto traces, BlastBufferQueue state is displayed through the following key metrics:

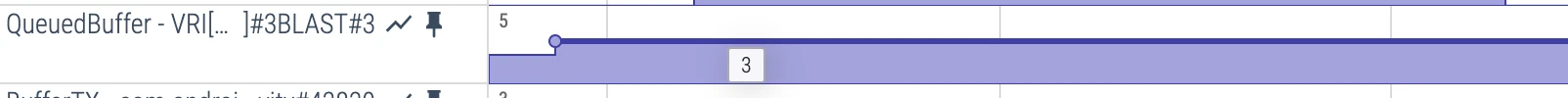

App-side QueuedBuffer Metric

- Perfetto display:

QueuedBuffervalue track - AOSP definition (BLASTBufferQueue):

QueuedBuffer = mNumFrameAvailable + mNumAcquired - mPendingRelease.size() - How to read it: This is a composite state metric, not a fixed-offset formula

- Practical use: Focus on trend and duration, not one instantaneous value

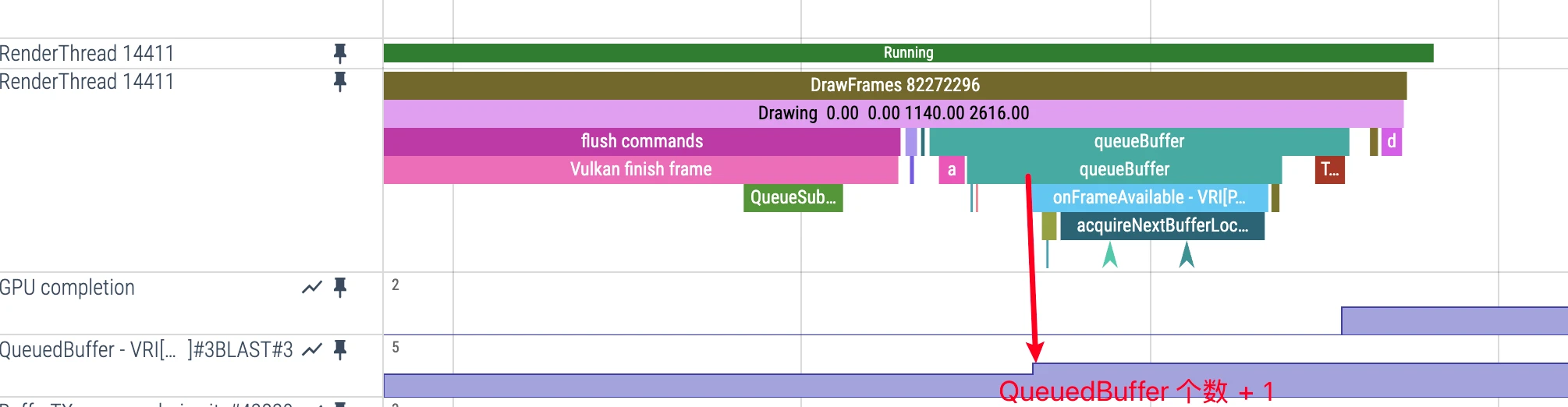

QueuedBuffer Value Change Timing

QueuedBuffer +1 timing:

- Common trigger: New buffer arrives into BLAST and becomes pending/processable

- Perfetto representation:

QueuedBuffertrack rises - Meaning: Frame pressure between app side and SF side increases

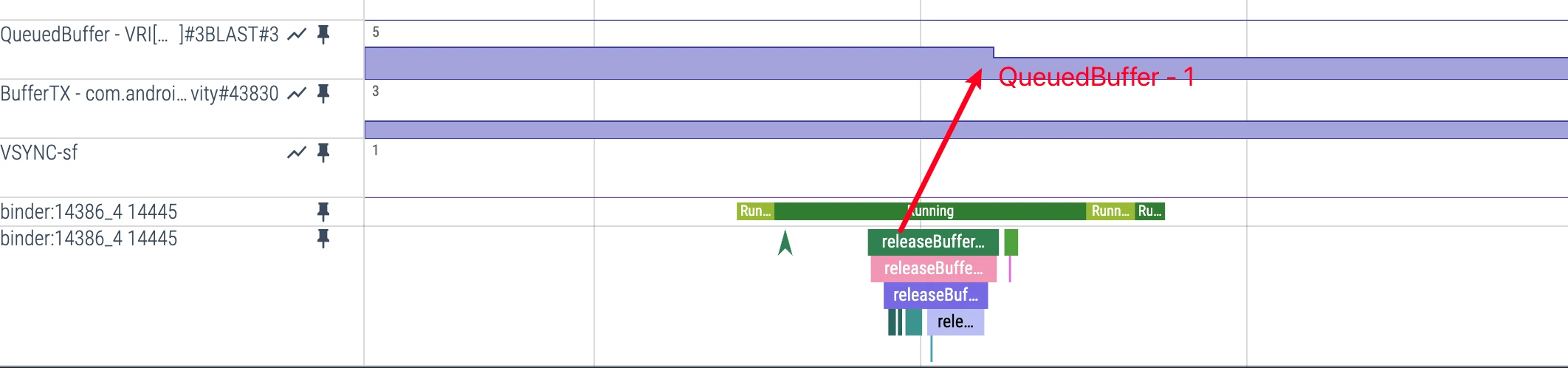

QueuedBuffer -1 timing:

- Trigger condition: Receives SurfaceFlinger’s

releaseBufferCallback - Perfetto representation: Can observe

releaseBufferrelated events - Meaning: A buffer is consumed/handled and released, queue pressure drops

SurfaceFlinger-side BufferTX Metric

- Perfetto display:

BufferTXvalue track in SurfaceFlinger process - AOSP definition (Layer): This tracks per-layer

mPendingBuffers; it increases when buffers arrive server-side and decreases when buffers are latched or dropped - Trigger condition: Depends on transaction and buffer lifecycle together; do not reduce it to “transaction received => +1”

- Note: It is not a universal fixed-max-3 metric; behavior depends on layer type, producer-consumer pacing, and system policy

Collaboration Flow Between App Side and SF Side

- App side: after frame submission,

QueuedBufferoften rises - Cross-process: BLAST/SurfaceControl transaction associates updates with frameNumber and enters SF-side processing

- SF side:

BufferTXchanges with pending-buffer lifecycle (arrive +, latch/drop -) - Backflow:

releaseBufferCallbackreaches app side andQueuedBufferfalls

Key Performance Observation Points

When analyzing performance, focus on:

- App-side QueuedBuffer trend: Continuous rise without fallback often means producer-consumer mismatch; correlate with main-thread

performTraversalsand RenderThreadDrawFramesto localize bottleneck - SurfaceFlinger-side BufferTX trend: Persistently high often indicates consumer-side pressure; persistently low while app keeps missing deadlines often points to producer-side starvation

Performance

If the main thread needs to handle all tasks, executing time-consuming operations (e.g., network access or database queries) will block the entire UI thread. Once blocked, the thread cannot dispatch any events, including drawing events. Main thread execution timeout typically brings two problems:

- Jank: If main thread + render thread execution for each frame exceeds 8.33ms (in 120fps case), frame drops may occur (saying “may” because in some cases frames won’t actually drop, due to app duration, buffer accumulation, etc.).

- Freeze: If the UI thread is blocked for more than a few seconds (this threshold varies depending on the component), users will see an “Application Not Responding“ (ANR) dialog (some manufacturers block this dialog and will directly crash to desktop)

For users, both situations are undesirable, so for App developers, both issues must be resolved before release. ANR is relatively easy to locate due to detailed call stacks; but intermittent jank may require tools for analysis: Perfetto + Trace View (already integrated in Android Studio). Therefore, understanding the relationship between main thread and render thread and their working principles is very important, which is also an original intention of this series.

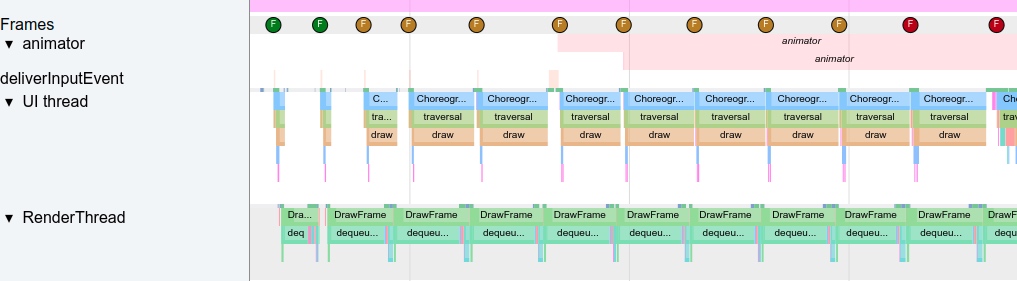

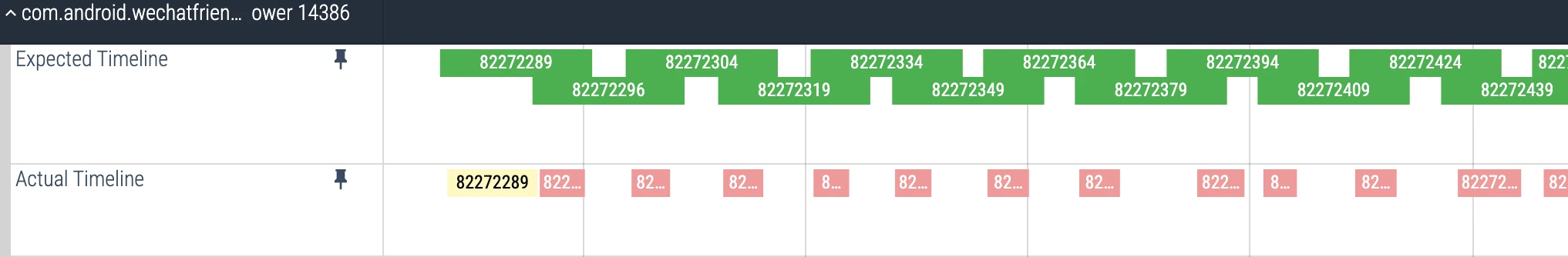

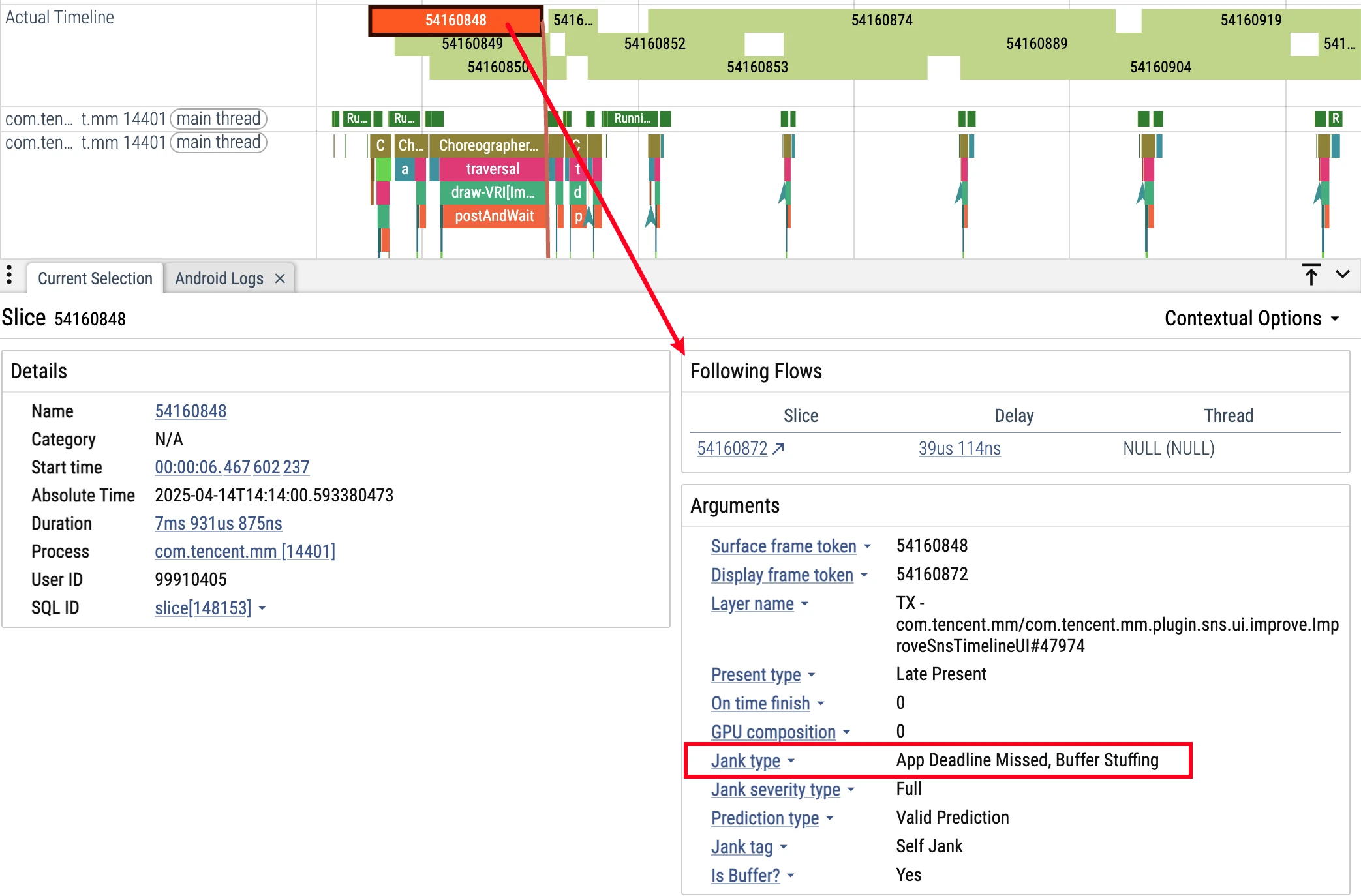

Perfetto’s Unique FrameTimeline Feature

An important advantage of Perfetto over Systrace is providing the FrameTimeline feature, which allows you to see jank locations at a glance.

Note: FrameTimeline requires Android 12(S) or higher version support

Core Concepts of FrameTimeline

According to Perfetto official documentation, jank occurs when a frame’s actual presentation time on screen doesn’t match the scheduler’s expected presentation time. FrameTimeline adds two new tracks for each application with frames displayed on screen:

1. Expected Timeline

- Purpose: Shows the rendering time window allocated by the system to the application

- Start time: When Choreographer callback is scheduled to run

- Meaning: To avoid system jank, the application needs to complete work within this time range

2. Actual Timeline

- Purpose: Shows the actual time the application completed the frame (including GPU work)

- Start time: When

Choreographer#doFrameorAChoreographer_vsyncCallbackstarts running - End time:

max(GPU time, Post time), where Post time is when the frame was submitted to SurfaceFlinger

When you click on a trace in Actual Timeline, it will show the specific consumption time for this frame (can see latency).

Color Coding System

FrameTimeline uses intuitive colors to identify different frame states:

| Color | Meaning | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Green | Normal frame | No jank observed, ideal state |

| Light green | High latency state | Stable frame rate but delayed frame presentation, causing increased input latency |

| Red | Jank frame | Jank caused by current process |

| Yellow | App-blameless jank | Frame has jank but app is not the cause, jank caused by SurfaceFlinger |

| Blue | Dropped frame | SurfaceFlinger discarded this frame, chose newer frame |

Clicking different colored ActualTimeline shows the following description in the info bar, telling you the cause of jank:

Jank Type Analysis

FrameTimeline can identify multiple jank types:

App-side jank:

- AppDeadlineMissed: App runtime exceeded expectations

- BufferStuffing: App sends new frame before previous frame presents, causing Buffer queue accumulation

SurfaceFlinger jank:

- SurfaceFlingerCpuDeadlineMissed: SurfaceFlinger main thread timeout

- SurfaceFlingerGpuDeadlineMissed: GPU composition time timeout

- DisplayHAL: HAL layer presentation delay

- PredictionError: Scheduler prediction deviation

Configuring FrameTimeline

Enable FrameTimeline in Perfetto configuration:

1 | data_sources { |

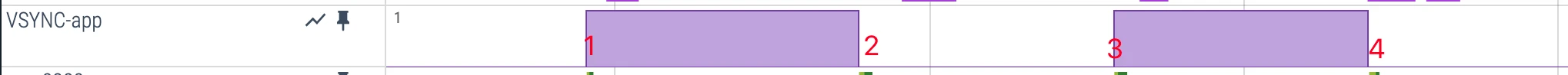

Vsync Signals in Perfetto

In Perfetto, Vsync signals are displayed using Counter type, which differs from many people’s intuitive understanding:

- 0 → 1 change: Represents a Vsync signal

- 1 → 0 change: Also represents a Vsync signal

- Incorrect understanding: Many people mistakenly think only becoming 1 is a Vsync signal

Correct Vsync Signal Identification

In the diagram below, time points 1, 2, 3, 4 are all Vsync signal arrivals

Key points:

- Each value change is a Vsync: Whether 0→1 or 1→0

- Signal frequency: On 120Hz devices, there’s approximately one change every 8.33ms (actual may vary slightly due to system scheduling, referring to continuous frame output scenarios)

- Multi-app scenario: Counter may remain active due to other apps’ requests

Analysis Techniques

Determining if App received Vsync:

- Correct method: Check if there’s a corresponding

FrameDisplayEventReceiver.onVsyncevent in the App process - Incorrect method: Judging solely by

vsync-appcounter changes in SurfaceFlinger

References

- https://juejin.im/post/5a9e01c3f265da239d48ce32

- http://www.cocoachina.com/articles/35302

- https://juejin.im/post/5b7767fef265da43803bdc65

- http://gityuan.com/2019/06/15/flutter_ui_draw/

- https://developer.android.google.cn/guide/components/processes-and-threads

Attachments

The Perfetto trace files involved in this article have also been uploaded. You can download and open them in Perfetto UI (https://ui.perfetto.dev/) for analysis

Click this link to download the Perfetto trace files involved in this article

About Me && Blog

Below is a personal introduction and related links. I look forward to communicating with you all. When three people walk together, one of them can be my teacher!

- Blogger Personal Introduction: Contains personal WeChat and WeChat group links.

- Blog Content Navigation: A navigation of personal blog content.

- Excellent Blog Articles Collected and Organized by Individuals - Must-Know for Android Performance Optimization: Welcome everyone to recommend yourself and recommend (WeChat private chat is fine)

- Android Performance Optimization Knowledge Planet: Welcome to join, thanks for support~

One person can go faster, a group of people can go further